Choosing a Scuba Regulator

How to choose a scuba regulator – A detailed guide on First Stages, Primary Regulators and Alternate Air Sources. In order for scuba divers to breathe underwater, they need to have a regulator in their mouth. A regulator is a critical piece of life support equipment. Regulators work on a demand system which delivers breathing gas to the diver, from the scuba tank, each time the diver inhales. All scuba divers carry redundancies with them for safety. As such, each diver needs to have a primary regulator from which they breathe, as well as an alternate air source which they can donate to another diver in need.

On first glance, it may seem like all regulators, and regulator configurations, are more or less the same. But there are actually some important differences between them which are worth considering when choosing a scuba regulator. When purchasing your own regulator, the most important considerations are comfort and ease of breathing. With an alternate air source, the important consideration is not only ease of breathing. Accessibility and being able to easily and quickly provide it to another diver, or switch onto it yourself in an emergency are equally important. In order to consider these factors, ideally, you need to dive with a specific configuration to see how it feels.

In this blog, we’ll consider some different regulators and their features but it is not exhaustive. If you have a question about a particular piece of equipment or would like to organise some diving with us and try some equipment, please contact us here.

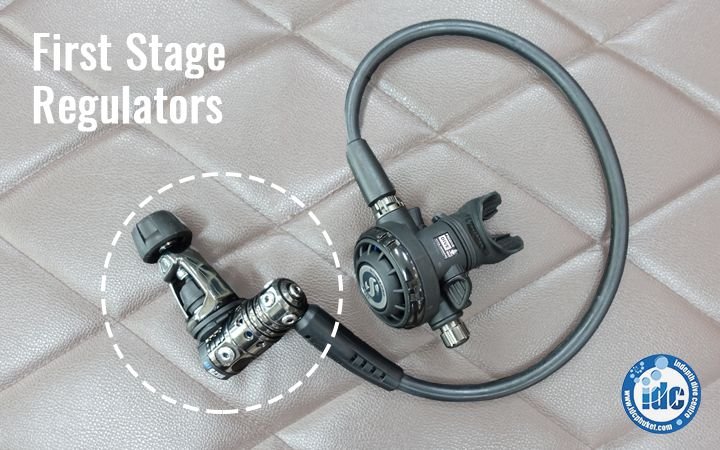

First Stage Regulators

Primary regulators and alternate air sources need to connect to a first stage regulator. It is the first stage which connects to the scuba cylinder and which delivers breathing gas to the regulators and to the diver as they inhale. The main function of the first stage is to reduce the high pressure of gas in the scuba cylinder down to a first, or intermediate pressure. The gas then flows to the second stage, or regulator at whatever ambient pressure the diver is at.

Piston versus Diaphragm First Stages

First stages are available in two different styles; piston and diaphragm. Although from the outside, they both look similar, it is the internal working parts which are different. All first stages have separate chambers within them separating the high pressure of the tank from the intermediate pressure gas. Although both work in a similar way, they have different parts inside.

First stages are available in two different styles; piston and diaphragm. Although from the outside, they both look similar, it is the internal working parts which are different. All first stages have separate chambers within them separating the high pressure of the tank from the intermediate pressure gas. Although both work in a similar way, they have different parts inside.

A piston first stage utilises a hollow piston and spring mechanism to allow the flow of gas. A diaphragm first stage utilises a thick rubber diaphragm instead. Both are equally high performing and responsive to the diver’s inhalations; making them both easy to breathe from. In situations that require a higher flow of gas, due to its design, the piston first stage performs better. In colder water, however, a diaphragm is less likely to freeze in the open position or cause a regulator free-flow.

Some forums argue one type of first stage is more expensive than the other with regards to maintenance and servicing. Similar arguments, however, can be found in favour of either style. Diaphragm designs have more working parts which may make them more expensive to service however the parts are generally easier to manufacture than those inside the piston first stage. A piston first stage has fewer moving parts but they need to align precisely in order to correctly function. Some argue this precision makes the piston design more expensive.

Din versus Yoke

The first stage needs to attach to the scuba cylinder and there are two possible options for this: either by a Yoke valve or a DIN valve. DIN stands for Deutsche Industrie Norm, after the manufacturer.

The first stage needs to attach to the scuba cylinder and there are two possible options for this: either by a Yoke valve or a DIN valve. DIN stands for Deutsche Industrie Norm, after the manufacturer.

On a yoke set up, the O-ring sits in the valve of the scuba cylinder. The yoke first stage then sits over the top of the O-ring and a clamp keeps it in place. This is the most common valve style in recreational diving, however, is impractical for technical or overhead environment diving as the clamp can bumped into obstructions and possibly dislodge.

The other style of attachment is a DIN valve and DIN first stage. On this set up the tank valve itself is hollowed out and the DIN fitting on the first stage is protruding, threaded and includes the O-ring. This is then screwed into the tank valve. DIN fittings are increasingly popular while more common in technical diving as they are more secure and streamlined. They can also handle greater pressures.

A scuba cylinder can be converted to accommodate both DIN and Yoke first stages through the use of either a DIN adaptor or by removing the insert from the tank valve itself.

Environmentally Sealed First Stage

For divers in cold environments, an environmentally sealed first stage is preferable. Cold water, combined with the cold, compressed air moving into the first stage can cause first stages to freeze open causing high-pressure gas to free-flow through the system and the regulator. An environmentally sealed first stage has a chamber filled with either oil, silicone, alcohol or a liquid which does not freeze. This creates a watertight barrier inside the first stage and allows the pressure inside the first stage to trigger the operation of the piston or diaphragm. An upside of an environmentally sealed first stage is that you can dive in cold water without risking a free-flow. Also, it protects the first stage from other environmental impacts like salt or sediments which may enter the first stage.

High Pressure and Low-Pressure Port Holes

All first stages include port holes on them. It is these ports where regulator hoses, low-pressure inflator hoses and submersible pressure gauge (SPG) hoses physically attach. The SPG is attached to a high-pressure port whereas other hoses, regulators and low-pressure inflators, are attached to low-pressure ports. Divers can also attach dry suit hoses and transmitters to their first stage via the port holes.

All first stages include port holes on them. It is these ports where regulator hoses, low-pressure inflator hoses and submersible pressure gauge (SPG) hoses physically attach. The SPG is attached to a high-pressure port whereas other hoses, regulators and low-pressure inflators, are attached to low-pressure ports. Divers can also attach dry suit hoses and transmitters to their first stage via the port holes.

The main difference between high- and low-pressure port holes is the high-pressure ports are exposed to the same pressure as what is in the scuba cylinder. The low-pressure ports are exposed to the intermediate pressure of the first stage. Most first stages have slightly different ports and hoses sizes for both high- and low-pressure attachments so divers reconfiguring their equipment themselves are unable to accidentally attach a low-pressure hose to a high-pressure port and vice versa.

An important factor when choosing a scuba regulator is also the number of port holes featured on the first stage. Most first stage regulators come with a total of 6 ports, 4 low-pressure and 2 high-pressure ports. This setup can accommodate pretty much any recreational diving configuration. However, some models of first stage regulators, especially the compact and lightweight ones made for travel like the Cressi MC5, only come with 3 low-pressure and 1 high-pressure ports. Such setup will not allow the diver to attach an additional low-pressure inflator hose which is needed for a drysuit. Then, having only 1 HP port will not allow the use of a tank pressure computer transmitter while at the same time keeping an analog SPG plugged in for redundancy.

Swivel Turrets

Although not commonly used for diving on a single, back-mounted cylinder, first stages attached to side-mounted tanks must include a swivel turret. Put simply, a swivel turret is part of the first stage itself. It is where the low-pressure port holes and the hoses are attached. This part of the first stage spins and allows the hoses to rotate around the first stage even whilst pressurised. This allows divers to streamline their hoses along their tanks during the dive but when they deploy their long hose to assist a diver in need, they are able to spin the hose around towards their buddy and allow them to access the full length of the hose without kinking it or inadvertently cutting off their gas supply. The swivel turret also allows the diver to position the short regulator hose in a way which optimises comfort.

Although not commonly used for diving on a single, back-mounted cylinder, first stages attached to side-mounted tanks must include a swivel turret. Put simply, a swivel turret is part of the first stage itself. It is where the low-pressure port holes and the hoses are attached. This part of the first stage spins and allows the hoses to rotate around the first stage even whilst pressurised. This allows divers to streamline their hoses along their tanks during the dive but when they deploy their long hose to assist a diver in need, they are able to spin the hose around towards their buddy and allow them to access the full length of the hose without kinking it or inadvertently cutting off their gas supply. The swivel turret also allows the diver to position the short regulator hose in a way which optimises comfort.

Choosing a Balanced or Unbalanced Regulator

While struggling on how to choose a scuba regulator, you may have heard the terms balanced and unbalanced regulators. Put very simply, a balanced second stage regulator breathes the same at any depth and at any tank pressure. In contrast, an unbalanced regulator may require slightly more breathing effort by the diver at greater depths or when the tank is low on pressure. Although on face value a balanced regulator may sound like the better option, there are some very high quality, high performing unbalanced regulators on the market and in reality, many divers cannot feel the difference between the two.

Balanced regulators are often more expensive to purchase and to service because of the different parts inside of them. Some forums argue a balanced regulator can go longer between services than what an unbalanced regulator can. However, we would not recommend testing this theory and instead would suggest you follow the manufacturer’s servicing recommendations. In order to see which regulator feels right for you, we recommend doing a dive with it first. Most dive and retail centres offer a variety of equipment and are happy to facilitate any requests they can.

Adjustable Regulators

Most second stage regulators have some form of adjustment on them. The diver can turn up or down the breathing gas flow delivered with each inhalation to suit their individual preferences. This normally happens through a dial or lever on the side of the regulator which the diver can adjust. It will allow the diver to optimise their breathing for maximum comfort and ease. The diver can adjust this mechanism during the dive so if for any reason they become exerted they have the flexibility to increase the amount of breathing gas they receive with each breath.

Materials – How to choose a Scuba Regulator

Most second stages and alternate air sources are made from highly durable, lightweight plastics, although other materials are also common. Some manufacturers such as Mares make some of their regulator models from metal. The reason is that metal has different thermal properties to plastic, making these regulators more suitable for cold water diving. Metal can, however, be heavy so for divers not diving in cold water. Mares also manufactures regulators made of ultralight techno-polymer as a lightweight alternative. The manufacturer Scubapro uses carbon fibre in some of its second stages which make these models ultra-lightweight and durable. These designs, however, are generally more expensive than the standard plastic variety of regulator.

Sizes – Choosing a Scuba Regulator

For some divers, particularly women and children, a standard second stage regulator can feel big and bulky in their mouths. Even if it’s made from a lightweight material such as plastic. Fortunately, some manufacturers offer regulators in smaller, more compact sizes. The manufacturer Aqualung, for example, makes the Mikron regulator which is about half the size of a standard scuba regulator and is ideal for smaller divers or those who just don’t like the bulkiness of other regulators.

Purge Buttons and Exhaust Valves

Purge Buttons – How to Choose a Scuba Regulator

All second stage regulators have a purge button that you can press to release gas from the scuba tank through the mouthpiece. You learn on your Open Water Course this is one of the methods to clear water out of your regulator. Not all purge buttons are the same though. On some regulators, the entire face is a purge button; sometimes made from very soft plastic which is easily depressed. On other models, only the centre of the regulator is the purge button and it is made from hard plastic. Some purge buttons are more sensitive than others and more easily depressed so we recommend testing different models and seeing what feels better for you.

Exhaust Valves – Choosing a Scuba Regulator

All second stage regulators also have an exhaust valve. As open circuit divers, we release the air we exhale out into the water as bubbles. The bubbles need to escape from somewhere which is from the exhaust valve. The exhaust valve is typically underneath the regulator mouthpiece, meaning bubbles rise up around the diver’s face with each exhalation. Some regulators like Apeks have a banana-shaped exhaust which moves the exhalation down and around the diver’s face so the bubbles don’t obstruct their vision. Some models of Hollis regulators use a single exhaust valve which is to the side of the diver’s face. If you are interested in any model of regulator, we recommend you try a dive with it to see how it feels and how it functions before you commit.

Standard Hose Lengths vs Long Hoses and Necklaces

Standard Configuration

When you choose a scuba regulator, most standard recreational second stage regulators come on standard hose lengths and this is what you would have seen, and learnt to use, on your Open Water Diver Course. The primary regulator is on a shorter hose which is around 75cm long. A slightly longer hose, usually 90cm, is used for the alternate air source. With this type of equipment configuration, the primary hose and regulator are designed to only be used by the diver and not to be donated to another diver. The slightly longer hose on the alternate air source is however designed to be donated to a diver who is out of air but not for that diver to continue to dive on.

You learn on your Open Water Course, once a diver is receiving assistance and breathing from an alternate air source, both divers need to immediately end the dive and safely ascend to the surface. This must be done in a vertical, facing position by which both divers maintain physical contact with one another, hence the length of the alternate air source hose is sufficient for this purpose.

Other hose configurations, however, are increasingly becoming popular in recreational diving. For this reason, some scuba training agencies have started teaching student divers to donate and receive both a primary regulator as well as a secondary alternate air source in out of air emergencies. This is so divers are prepared for buddies with any and all equipment types and configurations.

Long hose & Necklace Configuration

First used in technical and cave diving is the long hose which attaches to the primary regulator. This hose is 2.1m long; more than twice the length of a standard alternate air source hose. The purpose of having a hose this long is that a diver can donate it to another diver and can continue to dive on it, without needing to ascend. With a standard hose length and in recreational diving, the out of air diver must ascend. This is not possible on technical and cave dives as divers have decompression obligations or a physical ceiling preventing them from surfacing. They have no choice but to continue to dive out of the cave or to complete their decompression, even after aborting the dive.

Divers who dive with a long hose have their alternate air source on a shorter hose which sits around their neck on what is called a necklace. A necklace is a bungee cord or a purpose-made plastic loop holding the regulator just under the diver’s chin. In an emergency, the diver hands their buddy their primary regulator on the long hose and simply lifts up the alternate air source from under their chin, to their mouth.

This configuration also keeps the donor safer if the receiver suddenly grabs their primary regulator while starving for air. And this is what experts believe is likely to happen in a real and sudden “out of air” situation when the receiver is acting on instinct.

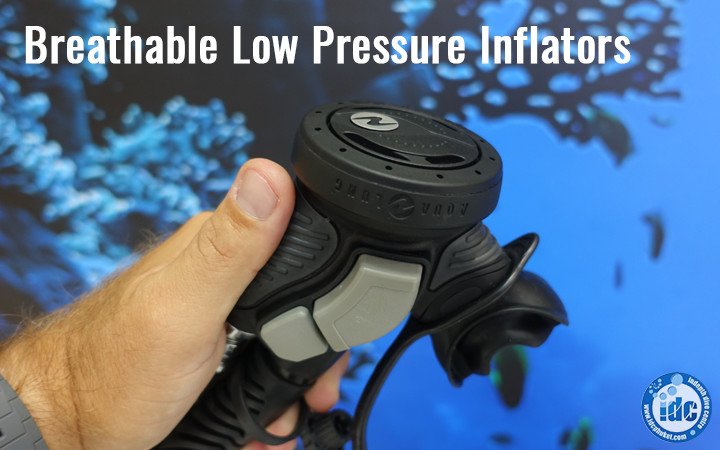

Breathable Low-Pressure Inflators

Some divers choose not to dive with a standard alternate air source and instead donate their primary regulator, on a standard hose, to their buddy in an emergency. These divers then switch onto a breathable low-pressure inflator (LPI), a regulator integrated into the LPI on their BCD. One of the downsides of this alternate air source configuration is that once a diver is breathing from it, it makes buoyancy control using the LPI difficult. In many instances, the diver needs to use a dump valve to vent air, instead of using the LPI. You may consider this option when you choose your scuba regulator.

Storing Alternate Air Sources

On most dives, hopefully, you will not need to use your alternate air source. As such, for the most part, the AAS will be placed of the way but still easily within reach. There are multiple options for how you stow an alternate air source. Some BCDs have dedicated pockets for them, other divers choose to clip them on to their BCD using quick-release attachments. Other divers clip their alternate air source to their BCD via the mouthpiece. The important considerations when attaching an alternate air source are that it is easily accessible, within reach, located within the triangle between the diver’s chin and their rib cage but also that it is streamlined and doesn’t pose a risk of entanglement or drag.

Hose covers, protectors and colours

Regulator hoses come with a protective cover to protect them from damage. Although most regulator hoses are ‘low pressure’ hoses, if they rupture, you’ll know about it. Hose covers are available in either plastic or braided webbing. Both styles are durable and long-lasting. A downside of the plastic hose cover is that over time it can begin to crack, especially where the hose bends such as where it attaches to the first stage. Likewise, the webbing hose covers can fray over time.

Hose covers are available in a range of colours, the most common is black for the primary regulator hose followed by yellow for the alternate air source. Other colours such as pink, blue, red, green etc. are also available. The main consideration for hose coverings is to ensure the hose itself is protected. Colour coverings also assure that other divers can easily identify the alternate air source.

For all hoses, where they attach to the first stage, they risk added wear in the places where they bend. As such, most hoses come with hose protectors which are rigid pieces of plastic which fit around the hose and sit against the porthole of the first stage and stops the hose itself from bending or wearing out. Like most pieces of scuba equipment, these are available in a variety of colours so you can colour coordinate your equipment if you want.

Mouthpieces – How to Choose a Scuba Regulator

A comfortable mouthpiece can make or break a dive. A mouthpiece which isn’t right for you can feel too small and like the regulator is going to fall out of your mouth. A mouthpiece which is too big can rub or cut your gums or the insides of your cheeks. Both can make the regulator leak and allow water to enter your mouth. If you feel like you have to chomp down to keep your mouthpiece inside your mouth, this can create jaw fatigue which is uncomfortable. Fortunately, all mouthpieces are interchangeable and there are lots of different options so you can find one which suits you. Some divers prefer the smaller mouthpieces which only sit around their front teeth whereas other divers prefer a longer mouthpiece which reaches back towards their molars.

Some manufacturer’s such as SeaCure have even created a mouthpiece which can be heated up in hot water, bitten down on and set into the shape of your teeth, like a mouthguard meaning it is personally fitted to you and your mouth, reducing the need for you to bite down on to it to hold it in place. Mouthpieces come in a variety of materials, most common is silicone which is generally a softer material and more comfortable.

Elbows and Ergonomic Swivels

Some regulators, even if light-weight materials, can feel heavy and pull down on the right-hand side of your jaw. This can contribute towards jaw fatigue over the course of a dive. One of the ways divers avoid this is by fitting their regulators with ergonomic elbows or swivels. These attachments sit between the regulator and the hose, allowing the regulator to bend or swivel where it connects to the hose. This means the regulator can sit into a more comfortable position in your mouth, placing less pressure on your jaw. The swivel attachments allow the regulator to freely move in response to the diver moving their head, providing optimal comfort.

Oxygen Cleaned Regulators

Not all regulators can be used for the same things. All standard scuba regulators are compatible with air as well as Nitrox mixes which contain up to 40% oxygen. They will not require you to do anything differently or change anything. Regulators intended for use with Nitrox mixes above 40% oxygen, however, need to be oxygen cleaned. Oxygen cleaned regulators are cleaned and serviced using lubricants compatible and safer for use with oxygen which is highly flammable.

If you do purchase an oxygen cleaned regulator, make sure you use it with the appropriate gases. If you do use it with regular air, it will need to be re-cleaned before being used with high oxygen content gases again. For any gas mixture you are using, you need to have undergone the proper training to use it. If you are interested in undertaking your Enriched Air Nitrox Course and learning more about different gas mixtures used in diving, click here.

Maintenance – How to Choose a Scuba Regulator

All regulators need servicing in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. At a minimum, you should service your regulator once a year. Regulators used frequently or which are showing signs of wear and tear, including leaks, need to be serviced more frequently. Not all regulators can be serviced by the same dive and retail centres. For example, an Aqualung regulator needs servicing by an Aqualung technician and a Scubapro regulator by a Scubapro technician. As a general rule, centres that sell a particular brand are authorised to service that brand.

Some retailers have dedicated equipment servicing programs and they attach tags to items such as regulators. The tag will indicate the date of when the next service is due. If you’re not sure what services your retailer provides though, ask. This is also a benefit of purchasing equipment in person versus buying something online. If you buy in person, you can verify and guarantee the ability to maintain that equipment in the future. If you buy something online which is not supported by a local retailer, you may have to send it away for maintenance which can be an added expense and may take more time.

With any piece of equipment, we recommend you try before you buy, and try as many different types as possible. If you have a question about a particular piece of equipment you are thinking about buying or would like to arrange some dives with us, please contact us here.